Primality testing in OCaml - part II

26 May 2022- Introduction

- Key ideas

- More detail

- Worked examples

- From probabilistic to deterministic

- An OCaml implementation

- Benchmarking against trial division

Introduction

In this post, we’ll implement a version of the Miller-Rabin primality test in OCaml and compare it to the optimized trial division is_prime function from our previous post. The Miller-Rabin primality test is a probabilistic algorithm for determining whether or not a given natural number is prime (though as we’ll see, it can be made deterministic in some cases). Understanding and implementing this test will require a few facts about elementary number theory.

Key ideas

There are certain number-theoretic properties that are guaranteed to hold for prime numbers. If one such property fails to hold for a given number \(n\), then \(n\) is composite. If many such properties do hold for \(n\), then \(n\) is likely to be prime. The two properties used for this purpose in the Miller-Rabin primality test are the following.

If \(p\) is an odd prime and \(a\) is any integer, then

- \(a^{p-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{p}\).

- If \(a^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{p}\) then \(a \equiv \pm 1 \pmod{p}\).

The first fact is just Fermat’s little theorem. The second fact follows from definitions: if \(a^2 \equiv 1 \pmod{p}\), then \(p\) divides \(a^2 - 1\), which factors as \( (a-1)(a+1)\). Since \(p\) is prime, this means it must divide one of those factors, hence \(a\) must be congruent to either \(1\) or \(-1 \pmod{p}\).

Now suppose \(n\) is an odd integer and we’d like to know whether or not it’s prime. To do this, we do a quick search for counterexamples to the above two properties. If we find one, then \(n\) is composite. If we can’t find one, then \(n\) is very likely to be prime. That’s the core idea behind the Miller-Rabin primality test.

More detail

Let \(n > 2\) be an odd integer, let \(2^s\) be the highest power of \(2\) that divides \(\nobreak{n-1}\), and let \(t\) be the quotient, i.e, write.

\[n - 1 = 2^s t,\]

where \(t\) is odd. Now choose an integer \(b\) (called a “base”), and compute the following powers of \(b \pmod{n}\):

\[\{b^{2^{s-1}t}, b^{2^{s-2}t}, \ldots, b^{2^2 t}, b^{2 t}, b^t\}\]

Note that each element of this list is found by squaring the element to its right \(\pmod{n},\) and finding the rightmost element is exactly what modular exponentiation is for. So even if \(b, t\) and \(n\) are large, this list should be easy to calculate. But how do we use this list to check whether or not \(n\) is prime?

Well, in light of the two facts above, we consider how this list must look if \(n\) really is prime. When \(n\) is prime, \(b^{n-1} \equiv 1 \pmod{n}\) by Fermat’s little theorem. Then the first element of our list is a square root of \(1 \pmod{n}\), so by property (2) listed above it must be \(\pm 1 \pmod{n}\). If it’s \(1\), then the second element of the list is \(\pm 1 \pmod{n}\). And if that’s \(1\), the third element is \(\pm 1 \pmod{n}\), and so on.

In other words, if \(n\) is prime, then for any \(b\) not divisible by \(n\) this list will begin with a sequence of zero or more \(1\)s, followed either by a \(-1 \pmod n\) or by the end of the list. So we can say:

Let \(n\) be an odd integer \(n\) and choose a base \(b\) not divisible by \(n\). Consider the list \[\{b^{2^{s-1}t}, b^{2^{s-2}t}, \ldots, b^{2^2 t}, b^{2 t}, b^t\}.\] If \(n\) is prime, then either some element of this list is \(-1 \pmod n\) or the rightmost element of this list is \(1 \pmod n\).

The contrapositive of this statement is a computationally easy test for compositeness of \(n.\) Since it’s usually the case that \(n\) is very large and \(b\) is very small, we can omit the divisibility condition.

Let \(n\) be an odd integer and let \(b\) be a base. Consider the list \[\{b^{2^{s-1}t}, b^{2^{s-2}t}, \ldots, b^{2^2 t}, b^{2 t}, b^t\}.\] If no element of this list is \(-1 \pmod n\) and the rightmost element is not \(1 \pmod n\), then \(n\) is composite.

The probabilistic version of the Miller-Rabin primality test works by choosing bases \(b\) at random and applying this test. If the test fails for some base \(b\), then we know that \(n\) is composite and we say that \(b\) is a “witness” for the compositeness of \(n\). But if the test succeeds for some \(b\) we say that \(n\) is a strong probable prime to base \(b\). If \(n\) is a strong probable prime to lots of randomly-chosen bases, then \(n\) is very likely to be prime.

Worked examples

Consider \(n = 17393\). To check if \(n\) is prime, we compute the above list for the base \(b = 2\), getting

\[\{1, 17392, 16624, 14940\}.\]

The second element is \(-1 \pmod{n}\). Repeating this with the base \(b = 3\) we get

\[\{17392, 769, 9480, 4305\},\]

and the first element is \(-1 \pmod n\). So \(n\) is a strong probable prime to bases \(2\) and \(3.\) In a vacuum, this would only be evidence leading us to suspect that \(n\) is prime. But it’s known that the smallest composite number that’s a strong probable prime to both \(2\) and \(3\) is \(1373653\). So here we can actually conclude that \(n\) is prime.

On the other hand, let \(n = 4033\). When we run this test with \(b = 2\), we get the list

\[\{1, 1, 1, 1, 4032, 3521\},\]

which begins with a sequence of \(1\)s terminated by a \(-1 \pmod n\), so \(n\) is a strong probable prime to base \(2\). But using \(b = 3\) we get the list

\[\{2443, 3442, 2443, 3442, 2443, 3551\},\]

and none of these terms are \(-1 \pmod n\) nor is the last term \(1 \pmod n\), so we conclude that \(n\) is composite. In fact, \(4033 = 37 \times 109\), though this factorization can’t be inferred by the Miller-Rabin test alone.

From probabilistic to deterministic

The Miller-Rabin test can show that \(n\) is composite by finding a witness \(b\) for the compositeness of \(n\). But even if it finds that \(n\) is a strong probable prime to many bases, that does not in general guarantee the primality of \(n\). But as we saw in the first example above, if we know that we’ll only be testing integers \(n\) below a certain bound we can pick a set of bases that makes the Miller-Rabin algorithm deterministic. For example:

- For \(n\) less than one thousand, it suffices to use the base \(2\).

- For \(n\) less than one million, it suffices to use bases \(\{2,3\}\).

- For \(n\) less than three billion, it suffices to use bases \(\{2,3,5,7\}\).

The important bound from a computational perspective is \(2^{64}\), the size of an unsigned machine integer. In this case, it turns out that using the first \(12\) primes as our set of bases will yield a deterministic algorithm. It’s possible (see here and here for examples) to find sets of bases with fewer than \(12\) elements that will still accomplish what we need, but that’s beyond the scope of this post.

An OCaml implementation

Finally, we’ll implement a (deterministic) primality test for machine integers in OCaml using the Miller-Rabin test. We’ll need a few utilities first. We’ll be re-using the tail-recursive range function from the earlier post, which we repeat here for completeness.

let range a b =

let rec range_aux a b lst = match b - a with

| d when d < 0 -> []

| 0 -> a :: lst

| _ -> range_aux a (b-1) (b :: lst) in

range_aux a b []

let (--) a b = range a b

We’re going to need integer exponentiation. Even though we only ever need small powers of two, we implement the general version.

let rec power a b = match b with

| 0 -> 1

| b -> let r = power a (b/2) in

if b mod 2 = 0

then r*r

else a*r*r;;

let ( ** ) a b = power a b;;

We’re also going to need modular exponentiation. It may be tempting to implement it similar to power above, with something like

let rec bad_powermod a b n = match b with

| 0 -> 1

| b -> let r = bad_powermod a (b/2) n in

if b mod 2 = 0

then r*r mod n

else a*r*r mod n;;

But this is not suitable for our purposes. If a, b and n are bounded by Sys.int_size, then we know powermod a b n should be as well. But the expressions r*r and a*r*r internal to the function can cause integer overflow. You have to be quite careful to work around this problem only using OCaml’s int type, and it’s really not worth the effort here. So in this case we’ll just use the Zarith library for multi-precision integers and save ourselves the trouble.

let powermod a b n =

Z.powm (Z.of_int a) (Z.of_int b) (Z.of_int n)

|> Z.to_int

When we write \(n - 1 = 2^s t\) for \(t\) odd, we need to know the highest power of \(2\) that divides \(n-1\), i.e. we need the exponent on \(2\) in the prime factorization of \(n-1\). This type of function has a name: It is \(p\)-adic valuation, and we implement it as follows.

let rec p_adic_valuation p n =

if n mod p <> 0

then 0

else 1 + p_adic_valuation p (n/p);;

let v_2 = p_adic_valuation 2;;

We’ll be using the first \(12\) primes as the set of bases for our implementation.

let small_primes = [2;3;5;7;11;13;17;19;23;29;31;37];;

We’ll also recycle our lazy has_element_with function from the previous post, which makes concise is_small_prime and has_small_divisor functions a bit easier.

let rec has_element_with pred lst = match lst with

| [] -> false

| x :: xs -> (pred x) || (has_element_with pred xs);;

let is_small_prime n =

has_element_with ((=) n) small_primes

let has_small_divisor n =

has_element_with (fun p -> n mod p = 0) small_primes

And that’s essentially all we need in order to implement our Miller-Rabin primality test. Our test for whether or not a given n is a pseudoprime to base b is internal to the body of this function, since we’re unlikely to ever need it elsewhere. This is nothing but a direct implementation of what’s outlined above. If n is very small, check directly if it’s a small prime. Otherwise, if n has a small divisor, then it’s composite. If n is large and has no small divisor, check whether or not it fails to be a pseudoprime to base b for any b in small_primes.

let miller_rabin n = match n with

| n when n < 38 -> is_small_prime n

| n when has_small_divisor n -> false

| n -> let s = v_2 (n-1) in

let t = (n-1) / (2 ** s) in

let is_pp_b b =

let rec is_pp_b_aux b i lst = match i with

| 0 -> let term = powermod b t n in

term = 1

|| term = n - 1

|| is_pp_b_aux b (i+1) (term :: lst)

| i -> let term = powermod (List.hd lst) 2 n in

if i = s

then term = n - 1

else term = n - 1

|| is_pp_b_aux b (i+1) (term :: lst) in

is_pp_b_aux b 0 [] in

let is_not_pp_b b = not (is_pp_b b) in

has_element_with is_not_pp_b small_primes |> not;;

And we can check correctness with simple testing, omitted here.

Benchmarking against trial division

The way we implemented trial division, we expect a runtime that looks like \(O(\sqrt{n})\), since the worst-case scenario involves testing a list of candidate divisors of length \(\frac{2\sqrt{n}}{3}\). But for Miller-Rabin, the worst-case scenario involved testing divisibility of \(n\) by \(12\) small primes, then testing whether or not \(n\) is a pseudoprime base \(b\) for \(12\) values of \(b\). Each of those tests involves a list of length at most \(64\). So we can technically say the runtime is \(O(1)\), though this is really a consequence of the fact that we wrote our algorithm to run on bounded inputs: things get more complicated if arbitrary inputs are allowed.

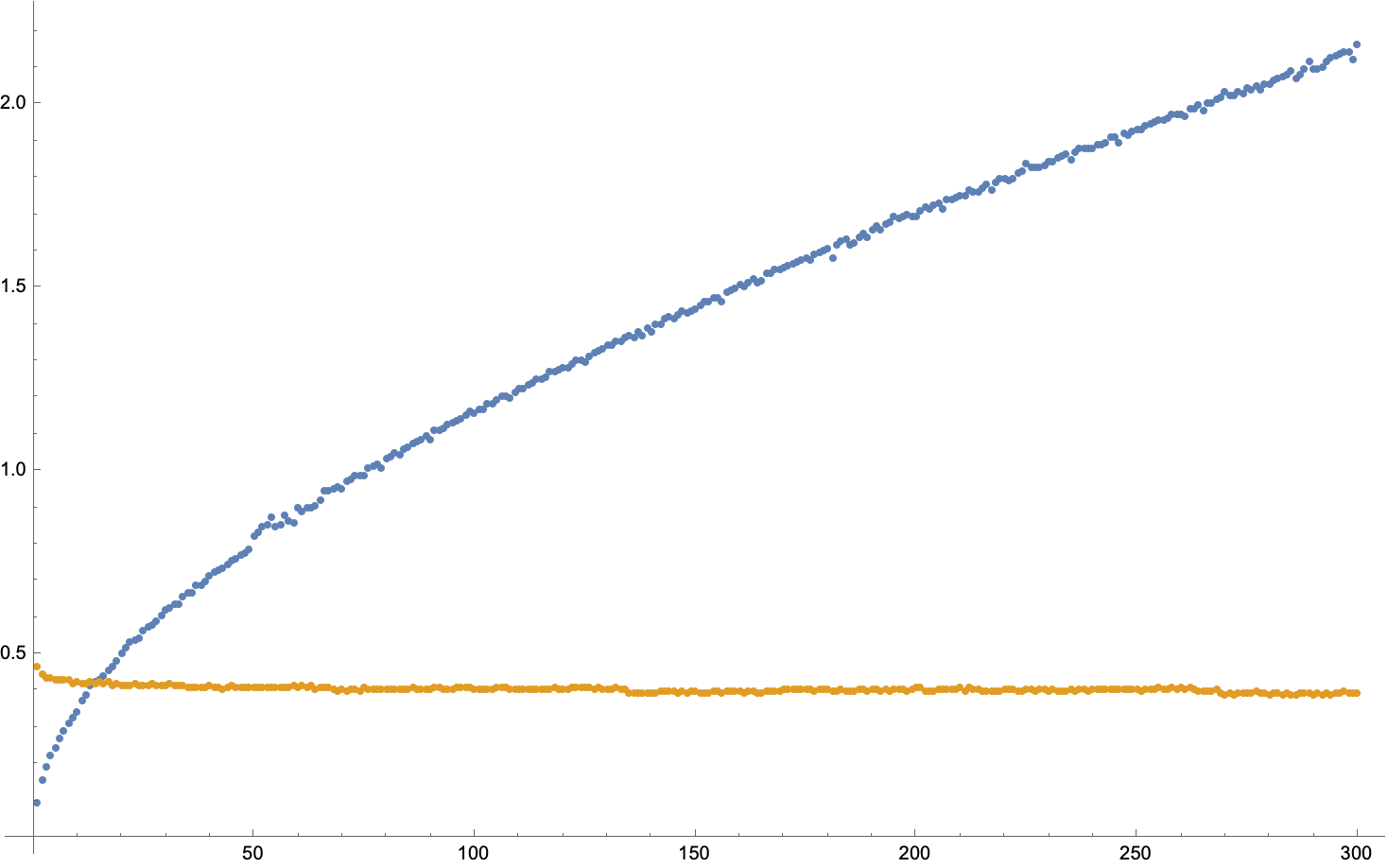

To get some hard data, we use both our is_prime and our miller_rabin to test the primality of the first 300_000_000 integers in batches of 1_000_000 at a time. In the graph below, the blue points represent how long it took is_prime to test the primality of integers in the range \([n 10 ^6, (n+1)10^6]\), while the yellow points are for miller_rabin.

It certainly looks like the runtime of is_prime grows like \(\sqrt{n}\), while the runtime of miller_rabin looks roughly constant. For this test, the total runtime for is_prime was 414.5, while the total runtime for miller_rabin was 129.6

For a different and more extreme comparison, we can test the primality of the largest prime that the int type can hold, which is 4_611_686_018_427_387_847. Trial division takes 14.5 seconds, while miller_rabin takes only 0.000035 seconds.