Conway's circle theorem and symbolic algebra

19 Aug 2022This post is about proving Conway’s circle theorem computationally, using symbolic algrebra and Mathematica. But before presenting this slightly unusual proof, we’ll start with a visual illustration of the theorem and a classical proof.

Conway’s circle theorem, visualized

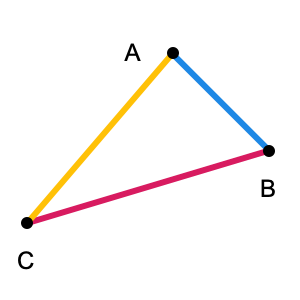

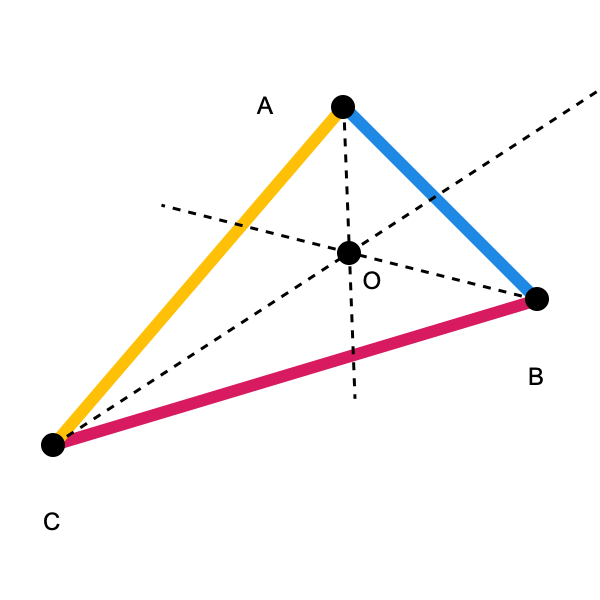

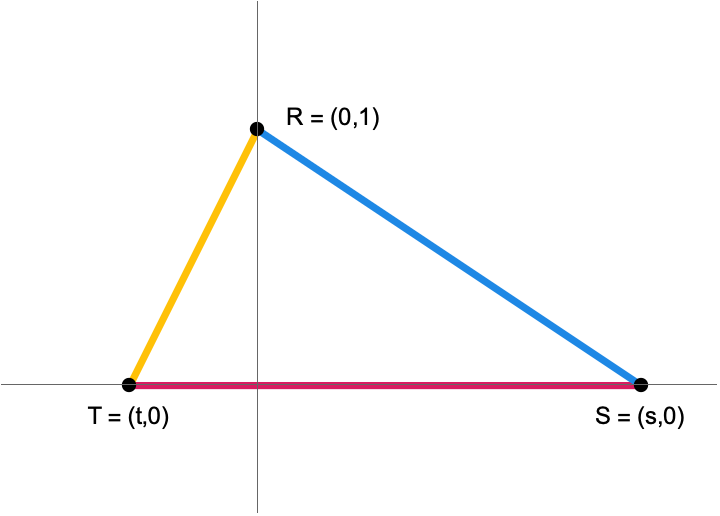

Consider a triangle \(\triangle ABC\):

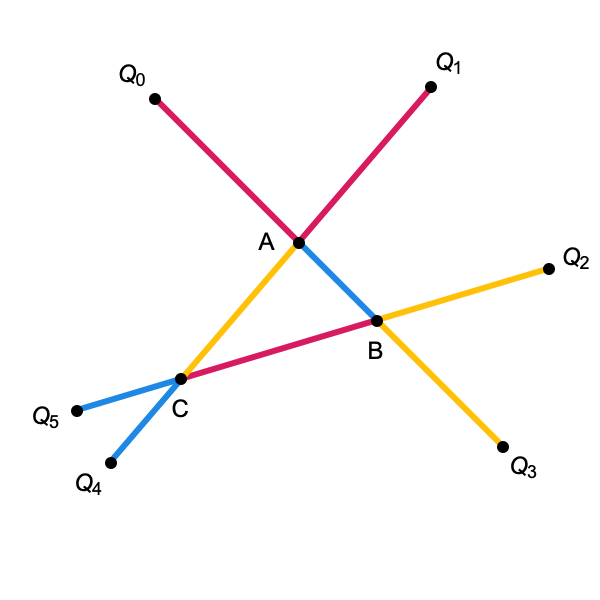

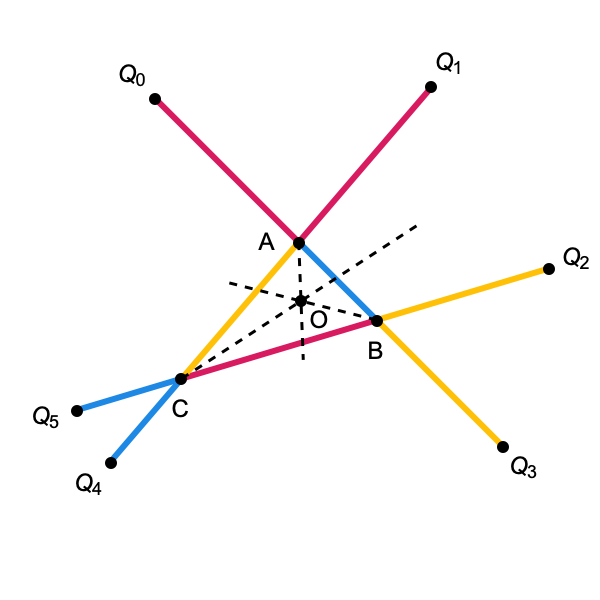

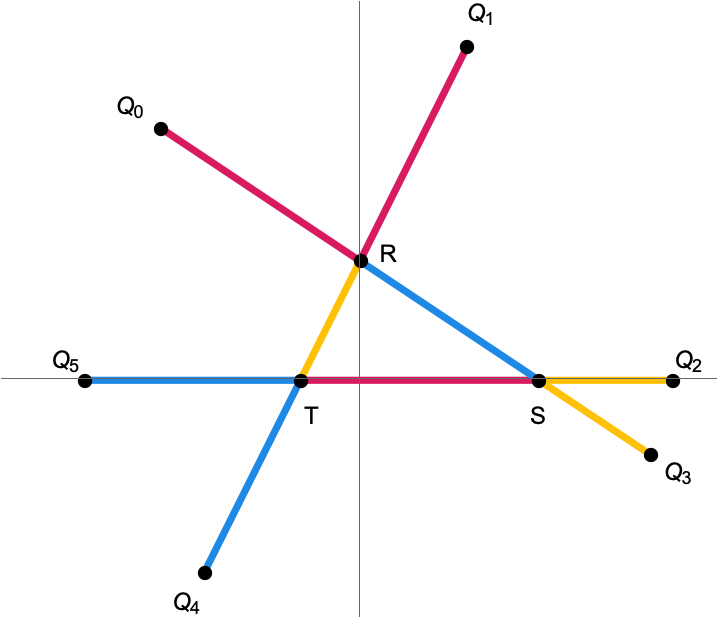

Now at each vertex, extend both of the incident edges by the length of the edge opposite that vertex. In the picture below, line segments of a given color have the same length. We’ll label the six the endpoints of these extended edges \(Q_0,Q_1,Q_2,Q_3,Q_4\) and \(Q_5\).

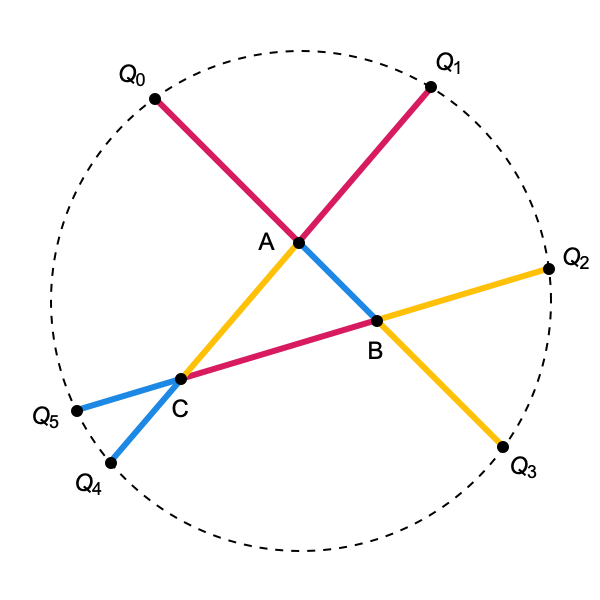

Conway’s circle theorem says that these six points lie on a circle.

For a more convincing visual illustration of this theorem, here’s an animation that shows what happens as the initial triangle varies:

A classical proof

Before proving this theorem computationally, we’ll first write down a more conventional proof. There are plenty of proofs of this theorem out there, including several “proofs without words”, see for example here, here and here. The simplest proof I’ve seen only relies on two elementary ideas:

- First, a very classical result: The angle bisectors of the interior angles of a triangle all meet at a single point, called the incenter of the triangle. We’ll use \(O\) to denote this point.

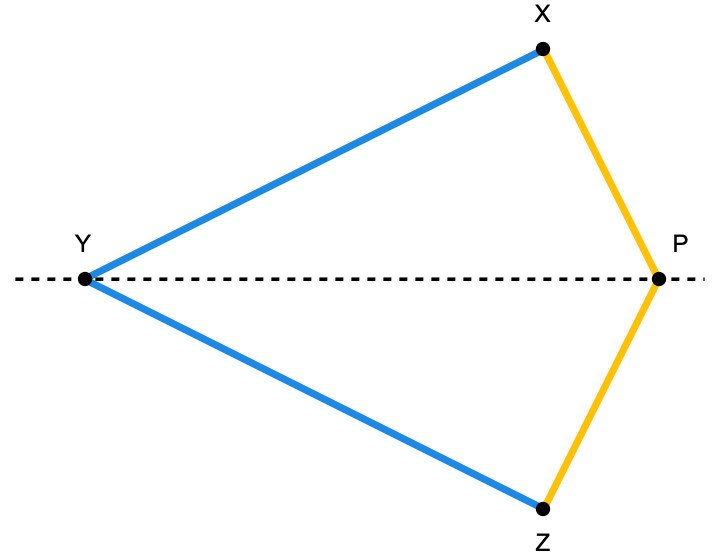

- Second, a tiny lemma: If \(\overline{XY}\) and \(\overline{YZ}\) are congruent line segments and if \(P\) is a point on the angle bisector of \(\angle XYZ\), then the line segments \(\overline{XP}\) and \(\overline{ZP}\) are also congruent.

Here’s how to use these two facts to prove Conway’s circle theorem (and let me stress that this proof is not new). After constructing the points \(Q_0\) through \(Q_5\), consider the incenter \(O\) of the given triangle.

The lemma implies that \(\overline{O Q_0}\) and \(\overline{O Q_1}\) are congruent. But it also implies that \(\overline{O Q_1}\) and \(\overline{O Q_2}\) are congruent, as well as \(\overline{O Q_2}\) and \(\overline{O Q_3}\), \(\overline{O Q_3}\) and \(\overline{O Q_4}\), and finally \(\overline{O Q_4}\) and \(\overline{O Q_5}\). So all six of the \(Q_i\) have the same distance from \(O\). So these six points lie on a circle.

A computer-assisted proof using symbolic algebra.

Here’s a very different method of proof, which I have not seen written down anywhere else. We’ll first translate the theorem into several algebraic statements. Then we’ll verify those statements using symbolic algebra in Mathematica.

First we note that we can rotate, translate, reflect and scale our initial triangle without losing any generality. This lets us assume that the triangle has one vertex at \((0,1)\) and two vertices \((s,0)\) and \((t,0)\) on the \(x\)-axis, with \(t < s\). In other words we lose nothing by placing our triangle in the \(xy\)-plane and assuming that it looks something like this:

In Mathematica, here are the coordinates of the three vertices.

R = {0, 1};

S = {s, 0};

T = {t, 0};

The six points \(Q_0,Q_1,Q_2,Q_3,Q_4\) and \(Q_5\) are constructed as described above:

We can also give explicit coordinates for these six points in terms of \(s\) and \(t\). For example, the coordinates point \(Q_0\) are given by

\[Q_0 = \overrightarrow{R} + \frac{\lvert \overrightarrow{ST} \rvert}{\lvert \overrightarrow{SR}\rvert} \overrightarrow{SR}\]

We could do this by hand to find that this point has coordinates

\[Q_0 = \left( \frac{st - s^2}{\sqrt{1+s^2}},1 + \frac{s-t}{\sqrt{1+s^2}}\right),\]

but there’s no need to do all that work. We can just generalize this vector expression and use it to get the coordinates of the six points in Mathematica where they’re much easier to work with.

q[{X_, Y_, Z_}] := X + Norm[Y - Z]/Norm[X - Y] (X - Y);

points = q /@ Permutations[{R, S, T}];

Now points is a list of the six points \(\{Q_0, Q_1, Q_2, Q_3, Q_4, Q_5\}\). To show that these points lie on a circle, we’ll do the following:

- Find the equation \(f(x,y)\) of a conic passing through the five points \(Q_1, Q_2, Q_3, Q_4\) and \(Q_5\).

- Show that \(Q_0\) also lies on the graph of this conic by checking that \(f(Q_0) = 0\)

- Show that \(f\) is the equation of a circle by inspecting its coefficients.

How do we find the equation of a conic that passes through five points? Recall that any two points in the plane lie on a line. One way to find the equation of the line passing through points \((a,b)\) and \((c,d)\) is to take the following determinant:

\[\operatorname{det}\def\arraystretch{1.5}\begin{bmatrix} x & y & 1 \\ a & b & 1 \\ c & d & 1\end{bmatrix}\]

This gives a linear equation in \(x\) and \(y\), and if you plug in \((a,b)\) or \((c,d)\) you get zero, since you’re taking the determinant of a matrix with a repeated row. So the determinant of this matrix is the equation of a line passing through the two given points. In a direct generalization of this fact, any five points lie on a conic. The equation of the conic passing through the five points

\[(a_1,b_1),(a_2,b_2),(a_3,b_3),(a_4,b_4),(a_5,b_5)\] is just the determinant of this \(6 \times 6\) matrix:

\[\def\arraystretch{1.5}\begin{bmatrix}x^2 & xy & y^2 & x & y & 1 \\ a_1^2 & a_1b_1 & b_1^2 & a_1 & b_1 & 1 \\ a_2^2 & a_2b_2 & b_2^2 & a_2 & b_2 & 1 \\ a_3^2 & a_3b_3 & b_3^2 & a_3 & b_3 & 1 \\ a_4^2 & a_4b_4 & b_4^2 & a_4 & b_4 & 1 \\ a_5^2 & a_5b_5 & b_5^2 & a_5 & b_5 & 1 \end{bmatrix}\]

for more or less the exact same reason. In Mathematica we can find the conic (with coefficients expressed in terms of \(s\) and \(t\)) passing through the points \(Q_1\) through \(Q_5\) by:

row[{a_, b_}] := {a^2, a b, b^2, a, b, 1};

f[{x_, y_}] := row /@ {{x, y}} ~ Join ~ points[[2;;]] // Det

By construction, the graph \(f(x,y)=0\) is a conic passing through \(Q_1\) through \(Q_5\). To check that it also passes through \(Q_0\), we only need to evaluate it at that point.

f[points[[1]]] // FullSimplify

We get 0, so the graph of \(f(x,y) = 0\) is a conic passing through all six points. But how do we know that \(f(x,y)=0\) describes a circle, and not an ellipse, hyperbola, parabola or a degenerate conic? Well, we can verify this with three straightforward algebraic checks. We just need to show that:

- \(f(x,y)\) has the same coefficient on \(x^2\) and \(y^2\).

- The coefficient on \(x^2\) is non-zero.

- The coefficient on \(xy\) is zero.

For notational convenience, let’s first give the implicit equation of our conic a one-letter name.

F = f[{x,y}]

Some of the symbolic computations that follow will only go through if we allow the engine to make use of the assumption that \(s\) and \(t\) are real numbers and that \(t<s\). We’ll also give those assumptions a name, for readability.

assumption = Assumptions -> {t < s}

Now to check (1), we take the difference of the coefficients on \(x^2\) and \(y^2\) and simplify.

FullSimplify[Coefficient[F, x^2] - Coefficient[F, y^2], assumption]

It simplifies to 0, so \(f(x,y)\) has the same coefficient on its square terms. Now we need to check (2), whether or not the coefficient on \(x^2\) is or could possibly be zero.

Solve[Coefficient[F, x^2] == 0, assumption]

We get {}, meaning that this coefficient is never zero regardless of the values of \(s\) and \(t\)

Finally, to check (3) we verify that the coefficient of the \(xy\) term is zero.

FullSimplify[Coefficient[f, x y], assumption]

And we do get 0. So with just 15 lines of code in Mathematica, we have shown that the six points \(Q_0, Q_1, Q_2, Q_3, Q_4, Q_5\) from Conway’s circle theorem lie on a conic which can be normalized and written implicitly in the form

\[x^2 + y^2 + A x + B y + C = 0.\]

Some elementary algebra shows that this is the equation of a circle. Since by construction its graph passes through multiple distinct points, it is non-degenerate. This completes the computer-assisted proof.